Three jobs in one is not sustainable for academics

Competing demands of research, teaching and admin take their pound of flesh

Picture this: I’m sitting in a big red armchair, slumped forward feeling numb and defeated, trying to explain to my psychologist why I’ve hit the wall. Sunlight fills the room through half-open Venetian blinds, but I’m in a dark place.

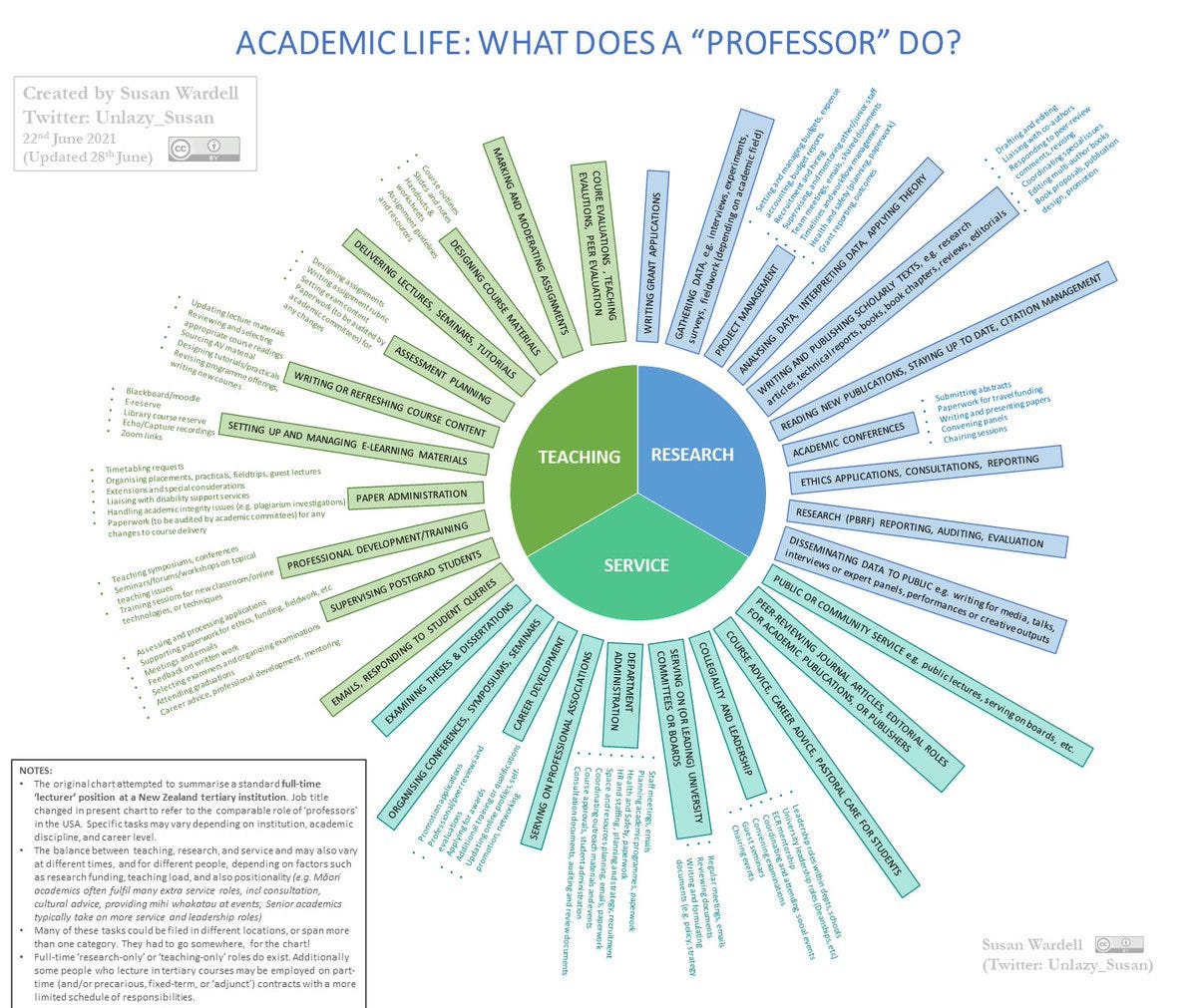

I show her this diagram illustrating the different roles and tasks of academic labour. Her response was one of astonishment:

“There is no way that any person can reasonably fulfil those requirements. It’s no wonder you are burned out!”

I could almost taste her sweet affirmation that the work expectations of my senior lecturer role were in fact outrageous. When you are constantly gaslit about the virtues of embracing an impossible grind, everything tastes like charcoal.

The various responsibilities contained in the academic workload across research, teaching and service clumsily integrate three very different jobs within a single role.

Imagine all the different tasks involved in across the research, teaching and admin roles, as illustrated above. Most of these tasks are mutually exclusive, even for a habitual multifunctionalist like me who likes to kill many birds with one stone.

Research, teaching and admin pull you in different directions. They are each based around different skills and competencies, a mix of linear bureaucratic process and non-meandering creative journey. Each requires mastery of different knowledge domains. Each has its own type of workflow, its own institutional logic, its own set of stakeholders, and its own unique set of performance metrics.

Those performance metrics bear only passing relation to the time required for their completion, and little relationship again with the weighting of prestige associated with professional success and career progression. And each year the workload expectations creep up and up and up.

On the one hand, what used to be called the teaching-research nexus is integral to lectureship. On the other, the cognitive load of attempting to manage these competing and contradictory demands is significant, and even more so for neurodiverse academics.

We jump between creative tasks and administrative routines, from solitary brain work to performing in front of a room full of students, between emails and committee meetings, and from the real world to Zoom and back again. None of these jumps is consequence-free. With each leap we lose a chunk of physical and emotional energy in the transition, let alone the energetic cost of each task itself. Jump enough times and you find yourself doing nothing well, though busy as hell.

Keep jumping around long enough and it will cost you a pound of flesh. The psychological and physical toll on academics is not a secret, it has been well documented for a long time.

Three jobs in one are not sustainable. Think it through, if you have any energy left.

Reflective lesson

You can’t recover from burnout without feeling the feels, without accessing the emotions that inhabit you in this dark place. That’s where the runes come in. For each article on this SubStack I will cast a rune to help me reflect on my experience from a Jungian archetypal perspective and, if I’m lucky, stride one more constructive step forward into a new and better life.

I’ve been reading runes for nearly ten years, and the practice has brought me comfort and clarity during times of difficulty. My reflection below was developed in dialogue with The Book of Runes by Ralph Blum.

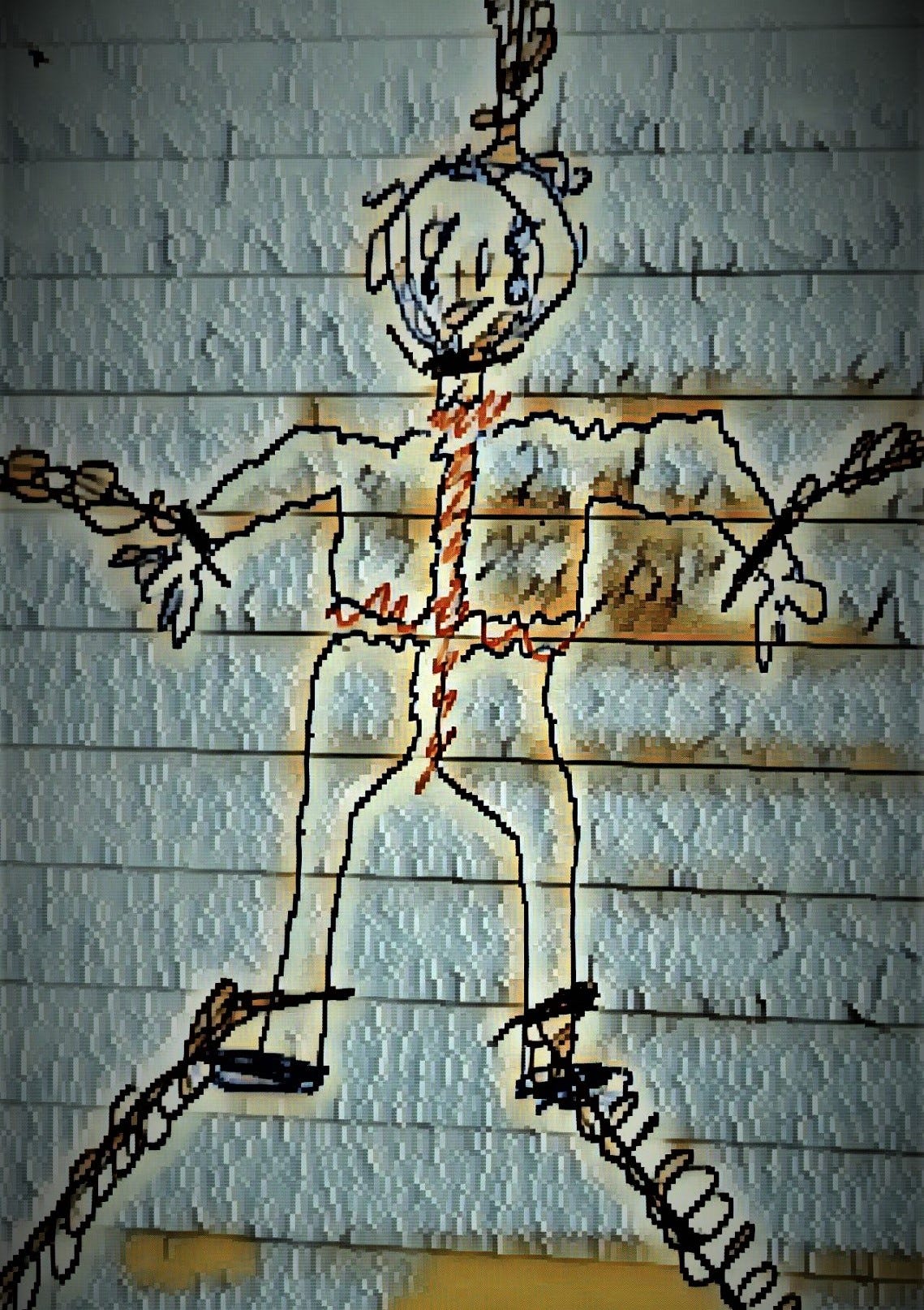

Rune: Nauthiz

Theme: Constraint as teacher. Pain as necessity. Resistance as fuel for transformation.

I pulled Nauthiz — the rune of constraint, necessity, and pain — as a reflection on this piece. It highlights the burden I was trying to name: the impossible contradictions of academic labour, the cumulative cost of context-jumping, and the slow but relentless siphoning of energy that came from being asked to split myself into three jobs and perform them all flawlessly.

Nauthiz doesn’t offer comfort, it offers clarity. Yes, the weight was real. At no stage were my feelings of depletion a sign of weakness. My discomfort was trying to tell me something. When I stopped trying to be good at everything and began listening to what the pain was trying to communicate, burnout became my teacher.

Nauthiz lays it out straight that I’d spent too long surviving on grind and grit, confusing endurance with integrity. Jaded and burned out, it became time to get honest about the truths I denied myself in order to be seen as a capable academic and the personal boundaries I betrayed to maintain the professional façade.

Nauthiz reminds me that my discomfort wasn’t punishment. It actually showed me the way out, freeing me from the illusion of over-identification with academic vocation, and from an institutional culture that can only thrive on the exploitation of my naive devotion.